Gallery contains 2 images

×

Photo 1 of 2

Combined Joint Task Force - Horn

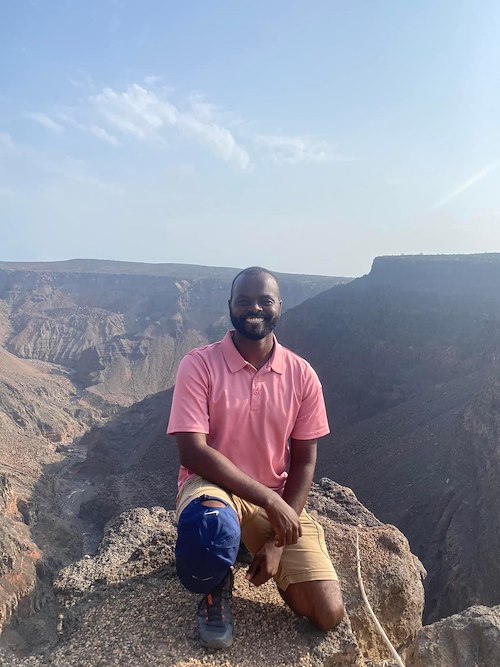

Hassan Ali is a native of Djibouti and became a U.S. citizen in 2012. He currently works for the Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa based on Camp Lemonnier, Djibouti. (Courtesy Photo)

Photo by: Master Sgt. Jerilyn Quintanilla

Photo 2 of 2

Combined Joint Task Force - Horn

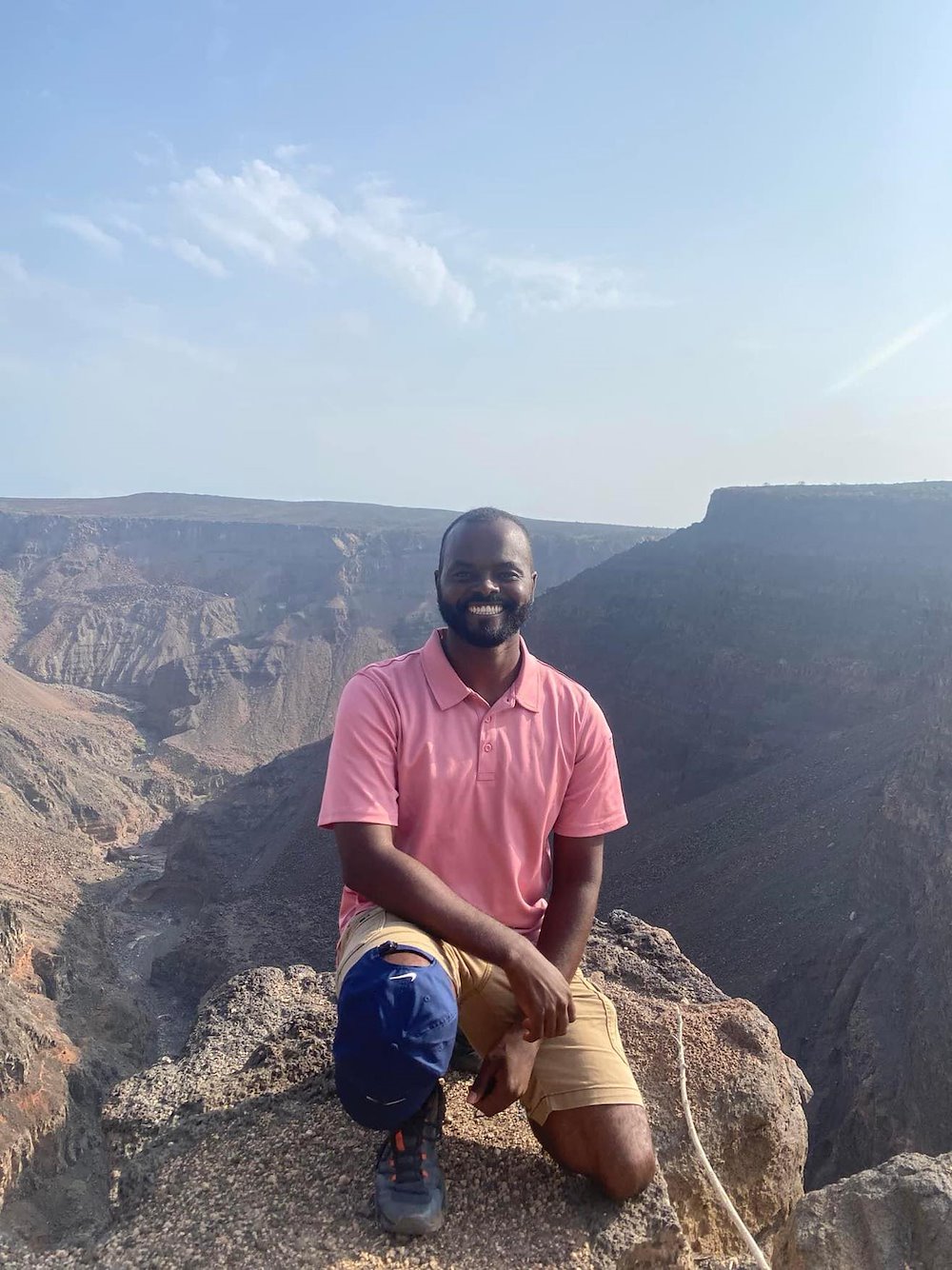

Hassan Ali is a native of Djibouti and became a U.S. citizen in 2012. He currently works for the Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa based on Camp Lemonnier, Djibouti. (Courtesy Photo)

Photo by: Master Sgt. Jerilyn Quintanilla

The Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa is, in every sense of the word, diverse. Service members and civilian employees of all different ages, hailing from every corner of the world with different outlooks and experiences are here serving a single mission. Among them is Hassan Ali, a resident of Virginia, a U.S. citizen since 2012, a member of CJTF-HOA, and a native of Djibouti.

Ali was born in Djibouti in October 1990 and his childhood he considered ‘typical for rural Djibouti’. He grew up surrounded by family and neighbors spending his days playing outside doing anything and everything, and sometimes nothing. He was unaware of the world outside of his small village but it was the only world he knew—or wanted.

“I remember waking up, the first thing we did every morning is we would run to go get fresh camel milk,” Ali said with a smile. “When I think about my younger years, we didn’t have much but we were happy. I had a mom that cared about me, I had siblings who cared about me and I had something to do every day. As long as I got to where I need to go every day I didn’t think anything else really mattered, I was happy where I was.”

The shift from his comfortable life in Djibouti to America was memorable to say the least. So much so that he remembers the exact day.

“May 5, 1998. We moved to Fargo, North Dakota of all places,” Ali recalled. “Everything [in Fargo] was so new to us so it wasn’t that we were in shock everything was just new. My brother wouldn’t let us out of the house. He was afraid we would get lost.”

Although not the most diverse city in the U.S., Fargo had a small-town feel which the Ali siblings took comfort in. It also exposed them to the different seasons for the first time which, for a kid born in one of the hottest countries on the globe, was unforgettable.

“Experiencing snow for the first time—I didn’t like it. It’s so cold!” he said shaking his head. “But once we figured out we could make a snow man that was really cool.”

As they all navigated the differences in climate and culture, Ali’s siblings went the extra mile to keep their Afar traditions and customs part of their daily lives.

“I think when you’re younger, kids like to show you you’re different, they like to tell you you’re different,” he said. “I felt like at home I was Afar. We would always speak Afar at home, we would always eat our culture’s food at home. My siblings did a very good job keeping our culture and traditions going.”

Today, Hassan believes immigrants are making a more considerable, visible effort to embrace one’s native culture as his siblings did.

“I think in the past, immigrants may have felt ‘we have to fit in, we have to assimilate’ and by assimilating you’re losing a big part of what makes you, you … your culture, your identity, your religion, your norms,” he said. “One thing I like about this current generation especially in the last 20 to 25 years is that we’re less willing to fully assimilate. America is a melting pot; it’s made of different cultures. I don’t think there’s one thing that is uniquely American.”

This perspective and appreciation for the diversity of the U.S., he acknowledges, comes in part from not having much of it in Djibouti.

“I came from a country where 99% of the people are the same, same culture, same religion same everything to a culture where everything is different and I’m meeting all these different people,” he said. “There’s beauty in that.”

In 2012, Ali was 22 years old, a recent graduate from South Dakota State University with a degree in political science and some experience working in Washington D.C., the epicenter of U.S. government and policy. He traveled back to Djibouti with the desire to give something back.

“I wondered, ‘How could I impart what I learned or experienced there, over here?’” he recalled. “There was a part of me that said, ‘I want to contribute to Djibouti’s progress.’”

This yearning to give back, he reveals, is not uncommon. In fact, he sees it as an “untapped resource.”

“There’s a lot of us from East Africa and West Africa who left when we were younger and grew up in the states who have knowledge of both worlds, both countries and who could really contribute,” he said.

More than a decade later, Ali’s worlds converged. He made his way back to Djibouti working for CJTF-HOA as a cultural advisor helping others learn and better understand his native culture, history, and lifestyle. In the last few years he transitioned to become a software integration lead for the Task Force directly supporting operations in U.S. Africa Command, realizing a personal goal he set as a teenager.

“When I was in high school I had the goal to work for AFRICOM in Djibouti one day,” he said. “I really care about our mission here at AFRICOM, and at CJTF-HOA. [These soldiers] all have families and children waiting for them and not seeing them for nine months or a year and they’re here working towards the mission. You have to appreciate that.”

Ali’s appreciation and gratitude for his work is evident in his attitude and demeanor. But it’s the people he is most thankful for.

“What job allows you to meet 300 people every nine months? Seriously?” he said. “I love this job because it allows me to train and interact with people and really get to know them. I think our stories are all really unique and they’re what help us connect as humans. I’m learning a lot from them and I think they’re learning a lot from me.”

Looking ahead at his future, Ali knows for sure that his experiences at CJTF-HOA will be marked not by metrics or tasks completed, but by the friendships made.

“I’ll remember my individual interactions with people,” he said. “And hopefully I was able to positively impact their views of Djibouti, and on Africa and Africans.”